From value judgments to cold calculation

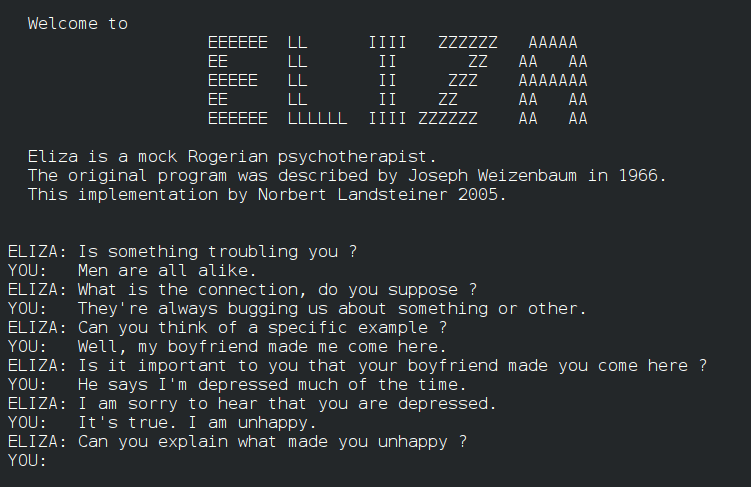

I'm finally reading this awesome portrait of the life and thought of Joseph Weizenbaum, the programmer of one of the first natural language chatbots called Eliza. In the 60's when Weizenbaum developed Eliza, he was basically part of the high priesthood of computer science, working in the newly founded "Artificial Intelligence Project" at MIT. The reactions that people had to his chatbot - insisting that it had intentions and intelligence - surprised him and made him deeply worried.

People were projecting something into the machine that was not there. This early version of a chatbot gave us a lesson about our human tendency to look for intentions behind the actions of all kinds of things - what philosopher of mind Daniel Dennett called the intentional stance. A psychoanalyst might call it transference.

With chatbot-induced psychoses and less-intense, but more widespread mesmerization by large language models (what the mesmerized call AI and which we should stop doing), it becomes clear how the intentional stance is causing a lot of confusion, which is fueling the "AI" bubble. Here, we can learn some valuable lessons from the story of Joseph Weizenbaum.

It wasn't until a few years later, when the Pentagon wanted to fund several new projects in Weizenbaums lab to help the American military murder people in Vietnam, that he had had enough. Pentagon had from the beginning funded the research, but now wanted to developing technologies that e.g. could balance a helicopter so a machine-gunner could more easily fire at people below. Weizenbaum split with the so-called "artificial intelligentsia" and threw himself into the anti-war movement. Later in the 70s he would write a book-length critique of the AI ideology called Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation.

The basic point of the book is that humans and machines are capable of different things - and thus are not interchangeable as the AI ideologists assume they (eventually) will be. Humans can guide their decisions by using values - what Weizenbaum calls judgement.

Values can by definition not be reduced to code.

Being into the philosophy and anthropology of values this makes a lot of sense to me. Values are the things that we can't explain the importance of by referring to something else.

With all other ways of evaluating action, you can always ask "Why is that important?" And someone will try to say "Because it does this or that". Which means their referring to something else that is important. And you ask again: "Why is that important?" And they will again say some other consequence or effect. On it goes. You might have had a similar conversation with a child. At some point you end up with something like "Because it is simply just beautiful" or "it is the right thing to do" or "that would be fair to everyone".

If someone would then ask "And why is that important?" and you wouldn't be able to answer - it might even seem preposterous to say why that is important (beauty, righteousness, fairness) - then you know you are in the presence of a value.

Values are by definition not reducible to other things. And they can't be explained or described in an exhaustive way.

Try describing beauty.

Sure, a lot of people have done so. Have they come up with the code? That would make it possible to automate the creation of beauty. Ask anyone who actually has a practice centered around the creation of beauty about the likelihood of coming up with a universal code for beauty. Wait for the answer.

(And please don't ask the question to a dimwit that spends all his life programming or calculating something and haven't painted or danced or sung a song or created anything that has aesthetically touched other people in his life, but is fully convinced that beauty can be automated. It is just embarrassing)

Or try describing justice. Sure, there are principles. They might even have some universality across cultures (and even species). But could you code it in a way that would end and cut through the complexity of human affairs? This is what liberals and lawmakers have spent hundreds of years trying to do. The law book gets thicker as the years go by and human life continues to overflow the courts with complexity.

In situations defined by values, at some point there has to be a judgement.

There's an expression that perfectly captures the limitation of coding: "Following the spirit of the law, not the letter of the law".

Weizenbaum's claim was that computers can't make decisions guided by values. They don't understand real values. They can only calculate. And they do that very well. If you give them a law, they will follow it to the letter. But nothing more than that. They won't get the spirit of the law, i.e. the values captured in it.

The problem is when you start giving computers tasks that are actually not calculating tasks but decisions that include value judgements. The computer will inevitably transform that judgement into a calculation.

We know this perverse transformation is possible because humans themselves routinely do it. Humans know how to calculate. We have many examples where humans turn value judgements into situations of pure calculation. I'm finishing up a translation of a book by David Graeber on the history of Debt right now and it is filled with stories about humans reducing complex situations involving value judgments to something more like cold mathematical calculation.

The very existence of debt and money is one case in point. Graeber defines debt as the perverse transformation of a commitment into cold calculation using violence. This is basically the same nightmare Weizenbaum was warning us against and that our abuse of computers could accelerate.

If we treat humans and machines as interchangeable, we reduce all value judgments to calculations. Our world will be filled with the perverse transformations of our commitments. The history of debt shows that can only be enforced through violence.